Description of the collaboration

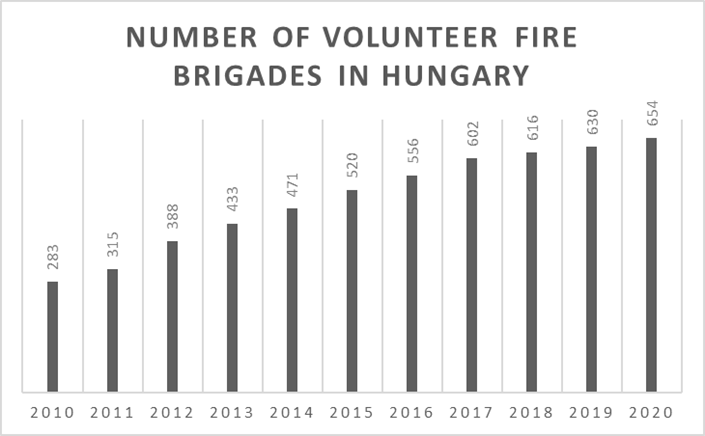

Although Hungary, as a country with a centralized public administration maintains national professional fire services, recent policy changes brought a large increase in the number of volunteer fire brigades, and an enhancement of their competences.

Figure 1: Number of volunteer fire brigades in Hungary. Source: Bérczi (2020) and Freedom of Information data request

The National Directorate General for Disaster Management (NDGDM) introduced the new status of ‘Responding Volunteer Fire Brigades’ (RFVB) for volunteer groups that could satisfy the strict eligibility criteria. By the end of 2020, 58 volunteer brigades had been certified as RFVB with a minimum of 3,000 hours on-duty time per annum. During their on-duty hours, RFVBs are fully integrated into the professional emergency system, and have at least four trained firefighters, standardized equipment, and the capacity for instant response. In exchange, central government provides them a monthly lump sum to cover parts of their operational costs (~500 EUR/month).

Impact of ICT on collaboration

The collaboration between volunteer brigades and the national disaster management agency is supported by various ICT solutions. NDGDM opened some governmental response systems to the volunteer brigades with the aim to fully integrate them into the overall coordination structure of the Hungarian fire and rescue services. They include (1) a central coordination system to alert and inform units about incidents, (2) a closed and encrypted radio communication, (3) and a standardized system for after-action reports.

- “PAJZS” is the central operation coordination system used by the National Directorate General for Disaster Management. It receives all calls in need of firefighting capacities.

- “EDR” is the nation-wide closed governmental TETRA radio system.

- “Disaster Management Data Provision Program’ (KAP) is an online application to send and manage reports and other administrative documents.

Many volunteer units use additional ICT services to support the collaboration, including smartphone applications to alert their members and disseminate information received from “PAJZS”.

Hungarian volunteer firefighters attending a reed fire

Impact of collaboration on efficiency

According to the interviews and the data received for this case study, Responding Volunteer Brigades make a big difference to the efficiency of the national fire and rescue services. Many of them cover more remote areas where the turnout time of professional fire units was unacceptably long. They not only reach an incident faster, but RFVBs can attend smaller accidents and fires without the requirement for on-site supervision from professional units. According to one informant, 10% of all alerts are now attended by volunteer brigades, either individually or as cooperating asset; this means 8,000 responses by volunteer brigades each year.

Table 1 shows that the on-duty hours of responding volunteer brigades have been constantly rising since 2014. During these hours, each RVFB must have at least four trained volunteer fire fighters ready to respond. Volunteer units offered readiness for 992,875 hours since 2014. Multiplied with a minimum of four members in a unit, this equates to 3,971,500 person hours. In comparison, professional firefighters work in 24 hours shifts with two days of break: with an average of 10 shifts/month. The average monthly gross salary for a professional firefighter is 270,000 HUF (800 EUR). Following this calculation, responding volunteer firefighters substituted salaries of 16,548 person months, equating to 4,467,937,500 HUF (around 13,2 million EUR).

Table 1: Number of Responding Volunteer Fire Brigades (RVFB) and their on-duty service hours.

| 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

| Number of RVFB | 12 | 22 | 37 | 44 | 49 | 55 | 58 |

| On duty (hrs) | 28 500 | 69 125 | 135 125 | 167 000 | 179 750 | 202 000 | 211 375 |

Source: NDGDM – Freedom of Information data request

There were 10,515 individual incident responses that were met solely by responding volunteer fire brigades since the introduction of this new level of collaboration (Table 2). Mobilizing volunteer units to these alerts, the new collaboration has shortened response times and cut the costs of the possible alert of professional units. Using the average response cost of a professional fire engine cited earlier, without the new responding volunteer structure, an additional 977,579,550 HUF (around 3 million EUR) would be required.

Table 2: Number of incident responses with VFB involvement. Source: NDGDM – public data request

| Year | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

| Number of incident response involving VFB assets | 3 903 | 3 923 | 4 746 | 7 711 | 5 582 | 7 496 |

| Number of RFVB responses without professional presence | 631 | 1 141 | 1 518 | 2 575 | 1 835 | 2 815 |

| Number of cooperating responses | 3 272 | 2 782 | 3 228 | 5 136 | 3 747 | 4 681 |

Impact of collaboration on red tape

Volunteer Fire Brigades work as local associations under Hungarian legislation. After the reform of the disaster management in 2012, the responsibilities and the role of volunteer units have been reframed. Each volunteer fire brigade must now establish a cooperation agreement with the relevant County Disaster Management Directorates (territorial bodies of the NDGDM). The agreement defines two-way responsibilities: the volunteer association takes part in fire and rescue activities led by the Disaster Management directorate, while they provide training and other opportunities to maintain and develop the fire and rescue activities of the volunteer brigade. A signed cooperation agreement is a requirement to apply for the annual call for proposals for training and equipment support, published by NDGDM.

The responding status of RFVBs comes with additional administrative responsibilities. As mentioned above, they need to issue after action reports following every deployment. They must register any changes in the status of their readiness into the system and maintain a stable radio connection (EDR) with the operations room, as they receive alerts through it.

Implications and lessons learned

Local volunteer fire fighting associations have become an important actor within the national fire and rescue system. This case study shows an example for the integration of local level private volunteer assets into a centralized governmental response system.

Policy changes and the introduction of the Responding status brought a larger financial support for local volunteer brigades; however, their financial background is still fragile. RFVBs receive a monthly lump sum for operational costs, but according to our informants, the 500 EUR does not cover the maintenance costs of the standardized fire and rescue equipment. Many local volunteer fire associations carry out fundraising activities, find donors among the local communities, cooperate with their municipalities, and participate in calls for proposals and project activities. In some cases, support from foreign (western) sister-settlements is also important, many volunteer fire brigades, for example, purchased or received equipment and fire engines as a donation from Austrian and German fire brigades. We conclude that the financial background of volunteer brigades needs to be strengthened in the future.

National governments and the county-based agencies have a critical role in building the trust needed for a good inter-organizational collaboration which can develop local resilience. The policy shift in disaster management supports the effective integration of local volunteer assets, leading to higher levels of community preparedness and resilience.

You can read the full case study here.

To read more about this research, see D9.1 – A Review of Efficiency and Red Tape in Public Sector Collaborations report.

Further materials/sources

- Hungarian Firefighter Association: 150 years

- http://www.tuzoltoszovetseg.hu/english

- http://tuzoltoszovetseg.hu/letoltes/document/431-150-years-of-the-hfa.pdf

- https://katasztrofavedelem.hu/application/uploads/yearbook/public/2018/en.pdf

- https://belugyiszemle.hu/teszt/en/node/673

About the Authors

András Molnár, Central European University

E-Mail | Homepage

Andrew Cartwright, Central European University