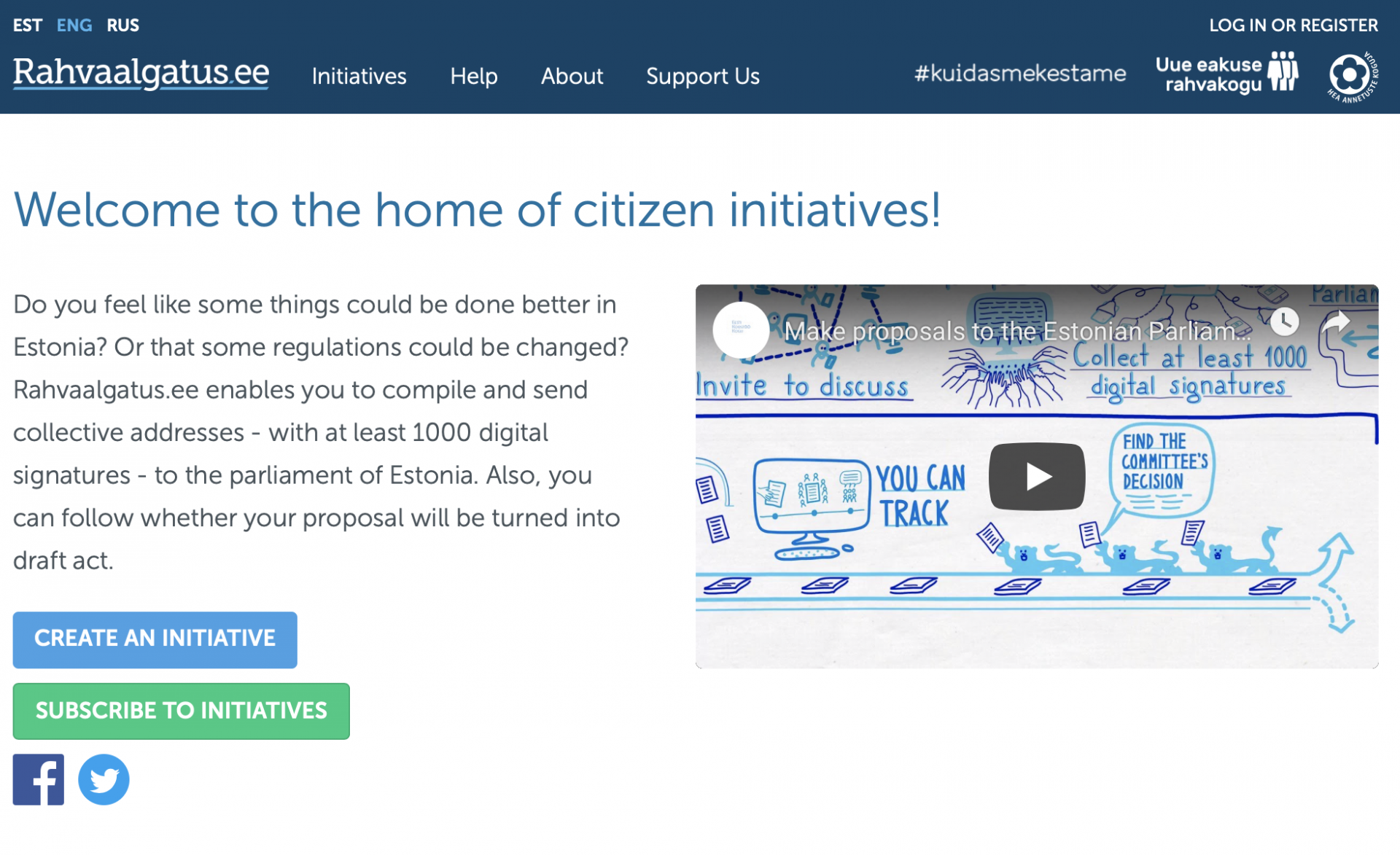

The Estonian Citizens’ Initiative portal (ECIP) is an e-participatory instrument allowing individuals to submit collective addresses to the parliament via an online platform. This encompasses proposing new ideas for laws and policies or suggesting changes to existing laws and policies. The e-participation portal is formally institutionalized through a cluster of laws and regulations addressing the processes pertaining to the platform, thus making it procedurally binding for the parliament. The formal proprietor of the portal is the Estonian Cooperation Assembly foundation, a competence center founded by the President of Estonia. The Cooperation Assembly is responsible for securing funding for the portal and dealing with the day-to-day management of the portal. The Cooperation Assembly collaborates with the Chancellery of the Parliament in determining the legality of the petitions and communicating the follow-up phase of the initiatives.

The Estonian Citizens’ Initiative portal (ECIP) is an e-participatory instrument allowing individuals to submit collective addresses to the parliament via an online platform. This encompasses proposing new ideas for laws and policies or suggesting changes to existing laws and policies. The e-participation portal is formally institutionalized through a cluster of laws and regulations addressing the processes pertaining to the platform, thus making it procedurally binding for the parliament. The formal proprietor of the portal is the Estonian Cooperation Assembly foundation, a competence center founded by the President of Estonia. The Cooperation Assembly is responsible for securing funding for the portal and dealing with the day-to-day management of the portal. The Cooperation Assembly collaborates with the Chancellery of the Parliament in determining the legality of the petitions and communicating the follow-up phase of the initiatives.

Aims and scope

The ECIP is a digital solution for exercising the legal right of Estonian citizens to petition the parliament. The ECIP is regulated by the “Response to Memoranda and Requests for Explanations and Submission of Collective Addresses Act”, adopted in 2014 with the aim of enhancing public participation in policy-making. The law stipulates the terms of handling citizens’ initiatives which gather at least 1000 signatures. All initiatives which qualify will be deliberated in parliamentary committees most relevant to the initiative. It is possible to present the signatures on both paper and online, and while some still use the option of collecting signatures manually, there is a clear trend towards digital initiatives becoming the preferred method for the citizens’ initiatives.

Implications and (un)intended effects

1. Legitimacy

The input side of democratic legitimacy is difficult to assess. Because of strict data protection policies, there is no public data about the demographic and socio-economic profile of the users of the platform. Throughput legitimacy of the ECIP is high, as it is quite rare that an e-participation instrument is backed by solid legal mechanisms. There is still room for development when it comes to transparency. While transparency is explicitly mentioned as a guiding principle on the web-page of the ECIP, there are still links missing between different parts of the whole process, the most problematic being the follow-up phase. Because there are a number of options how the parliament decides to process the initiative, it is very difficult to design a comprehensive and user-friendly view of the output side of the e-participation initiative. Output options are determined by law, and there are six of them:

1) the responsible parliamentary committee can initiate a bill or draft resolution on the issue, when they reach an agreement on the changes necessary, which will then be voted upon in the parliament;

2) the committee can hold a public sitting, where anyone is welcome to join;

3) the committee can forward the initiative to the competent institution (agency, board, department or local government office) for taking a position and resolving the issue;

4) the committee can transmit the initiative to the Government of the Republic, which is instructed to develop a position regarding the proposal and is obliged to notify the commission of their resolution;

5) the committee can reject the proposal; and

6) the committee can resolve the initiative “through other means”.

2. Efficiency and Effectiveness

The digital solution for gathering signatures for citizens’ initiatives is lightweight both in terms of financial as well as human resources. The portal is administered by the Estonian Cooperation Assembly, which employs one person to manage the portal. All technical running costs are covered by micro-donations by the users of the portal. The input from the portal is inserted into existing policy-making processes. Profuse lawmaking is often a problem of modern democracies, which is why it is complicated to measure the effectiveness of the ECIP by whether it results in new laws and policies or not. However, it is possible to gauge whether the ECIP has influenced the agendas of the parliamentary committees, and whether the subjects which come through the ECIP receive special attention when compared to issues which end up on the committee’s agenda through other means. Regarding the influence of the ECIP over the committees’ agendas, it is quite clear that this influence is substantial. Because of the precise procedural regulations, it is not possible for the committees to ignore the initiative, draw out the process indefinitely, or bury the proposal until the next election. The procedural regulations contribute to clarity of process, thus creating a certain level of trust between the citizens and the parliament.

3. Politics-Administration Dichotomy

The ECIP presents an interesting case of “participatory parliamentarism”. Often the notion of participatory policy-making has been associated with the executive branch, as the executive branch has usually been made responsible for organizing participatory processes for engaging the civil society. In the case of the ECIP, the parliamentary committees which receive citizens’ initiatives organize such participatory practices themselves by coordinating roundtables, which involve the authors of the initiative, as well as representatives from relevant administrative units and the private sector. By doing this, the parliamentary committees become the central coordinators in participatory policy-making processes.

To read more about the case study, see D5.1 – Comparative case studies on e-participation report.

Further materials

- Website of the Estonian Citizens’ Initiative portal. Available here.

About the Author

Kadi Maria Vooglaid, Tallinn University of Technology

Tiina Randma-Liiv, Tallinn University of Technology